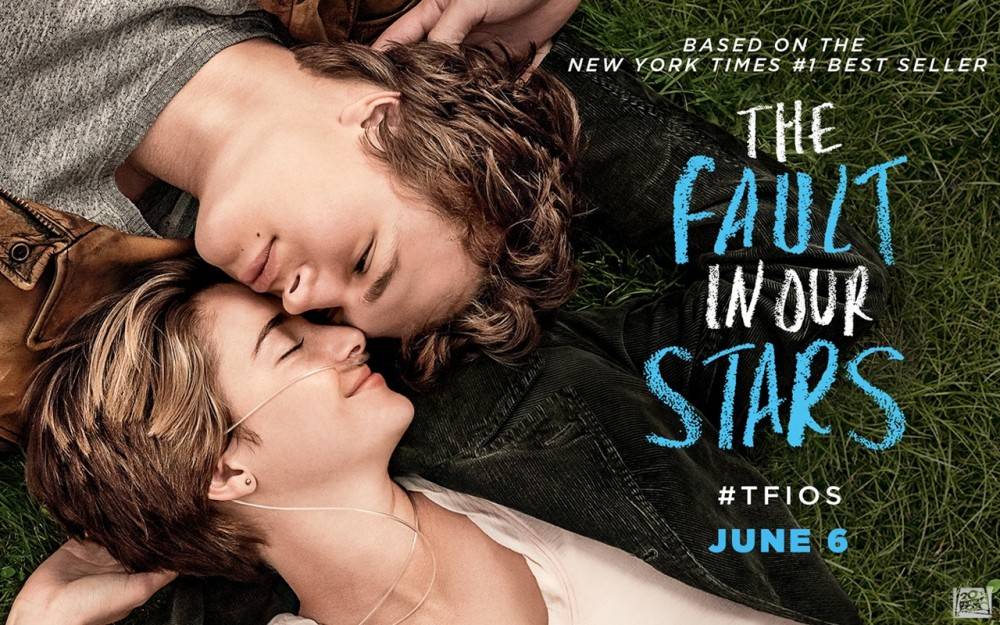

Earlier this week, I had the opportunity to attend an advance screening of the film The Fault in Our Stars, based on the novel of the same name by John Green. I had thoroughly enjoyed the book (as much as one can enjoy a book about kids dying from cancer), and although I had a few reservations about the film’s cast (having recently watched Shailene Woodley and Ansel Elgort, TFIOS’ star-crossed lovers, play siblings in Divergent), they were mostly dispelled when I attended the Demand Our Stars event in Nashville last month.

Naturally, I went into the movie pretty excited. I knew the film had the resounding support of author John Green, the cast was made up of enthusiastic fans of the book, and the few people I’d talked to who had already seen it unanimously agreed that it was an excellent adaptation. So armed with a TFIOS-themed packet of tissues, I settled into my seat for what I guessed would be a solid two hours of sobbing.

Nutshell reaction:

The early reviews were right. This movie is well cast, beautifully acted, expertly scored, and faithfully adapted. Book fans should be extremely pleased, and those who haven’t read the book will walk away with tear-streaked faces and a solid understanding of what all the fuss is about.

Longer reaction:

From the opening scenes of the film, it’s evident that everyone involved in this production was trying to be true to the spirit of the book. Everything from the script to the costumes to the set design seemed lifted straight from the pages. That dedication carries through the entire film, and nearly all of the tentpole lines and scenes are present and accounted for (one notable exception being the lack of the Shakespearean reference from which the story draws its title, but considering the indifference to the source material that often happens when translating a book into a film, such small omissions are forgivable). The tone also carried through, which was no small task. This is a story about kids with cancer, and in some cases kids dying of cancer, but never becomes maudlin. It’s interspersed with levity and humor and the kind of irreverent joking — from both the teens and the adults — that make it more a story about family and friendship and first love and growing up than a story about cancer.

Although I had my doubts about the chemistry between the two leads, Shailene Woodley and Ansel Elgort won me over with genuine performances. The dialogue in the book was often flowery and a bit pretentious, and I’ve often heard critics bash it with the claim that “no one talks like that, especially not teens.” (The fact that I knew teens who talked and thought very much like this just proves how much of a story’s believably relies on the consumer’s personal experience, which is an element totally outside of the writer’s control — but that’s a topic for another time.)

My point is that the two young actors, and Ansel Elgort in particular, did an excellent job of portraying exactly the sort of person who would talk like this. He would probably think of himself as loquacious, not necessarily pretentious; at one point, he asks Shailene Woodley’s character, Hazel, not to interrupt him in the midst of his “grand soliloquy,” which is a perfect example of just how much his character, Gus, likes to hear himself talk. He played it in such a way that I could feel the character’s need to matter, to say something worthwhile, in an effort to thwart “oblivion,” which is Gus’ worst fear. It made me wonder if Gus would be prone to such epic monologues if cancer never found him. Maybe. But it was questions like this, along with little touches like his insecurity about his amputated leg, or his initial fear and then subsequent childlike wonder at his first time on a plane, that kept him from becoming a caricature.

Shailene Woodley is a bit of an anomaly for me. I can never picture her as the characters she gets cast as, but then when I see her performance, she wins me over. She’s one of those actors that never seems like she’s acting, which may be why I always have a hard time imagining her outside her most recent role. Hazel was no exception. Her portrayal of a teen living with cancer is compelling and authentic, and she’s able to infuse lightness and humor into the role while never downplaying the gravity of the situation (the oxygen tank she has to cart around for the entire movie is a constant visual reminder of her struggle, but even if the tank wasn’t there, the tightrope Hazel has to walk between “normal teen” and “cancer kid” is always present).

Then Nat Wolff fills out the teen cast as Isaac, who starts the film with one working eye and ends it with zero. His role is reduced from what it is in the book, but he is able to make the most of the screen time he’s given, stealing every scene he’s in. While also a kid suffering from cancer, Isaac’s biggest struggle in the movie isn’t the loss of his sight, but the loss of his girlfriend, which adds both levity (as Isaac works through his frustration by smashing Gus’ basketball trophies — with Gus’ blessing, of course — and by egging his ex’s car, in full view of her mother), and perspective: These are kids living with cancer, emphasis on living. They have cares and hopes and struggles and heartbreaks that have nothing to do with their illness, even when it takes their eyesight, or their leg, or their ability to breathe.

As in the book, the parts that got to me the most weren’t the parts with the teens — though several scenes, particularly the fake-funeral, predictably tugged on the tear ducts — but the ones with the parents. This is probably because I’m an adult, and a parent, myself, but even teens or adults with no kids should be able to empathize with the powerful adult performances in the movie. The one with the most screen time is Laura Dern, playing Hazel’s mother, but pretty much every scene where we get a glimpse into Hazel’s and Gus’ parents struggle as they watch their children fight their diseases was heart-wrenching. There were very few parent scenes that I made it through with dry eyes, and the fact that Laura Dern and Sam Trammell (playing Hazel’s father) could convey so much with a quiver of their chin or a sideways glance made their strength and their grief beautifully palpable.

Much like the book, The Fault in Our Stars is sad, but not melancholy; romantic, but not sappy; heartwarming, but not saccharine. It sensitively addresses hard questions, like is it possible to live fully while you’re dying, or can a parent still be a parent once their child is gone, without providing easy answers. The performances are sincere, the film making is straightforward, and the lessons are layered. It’s a film about kids with cancer without being a cancer film, where even the sickest characters are defined by so much more than their disease.

Augustus has a line early on in the film when he asks Hazel, “What’s your story?”

She starts in, “Well, I was diagnosed when I was thirteen…”

And he interrupts her, “Not your cancer story. Your real story.”

I think that line is one of the main themes of the movie, and the book. There’s the cancer story, and then there’s the real story. I thought the film did an excellent job of focusing on the real story.